Fingerprints

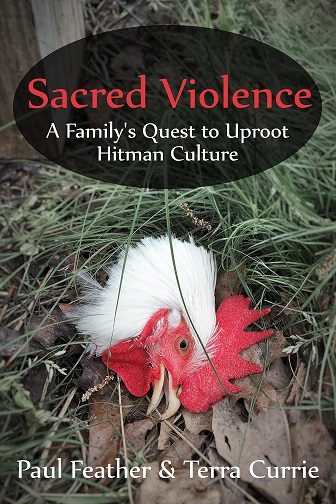

When I was about twenty-one, I got a job at the Laboratory for Atmospheric and Space Physics (LASP) testing sensors destined for orbit around the planet Mercury. There aren't any repair shops up there, so it's worth paying students to bake your instruments in an oven and make sure they'll still read accurately when they're halfway between Earth and the Sun. The sensors I tested would be installed on a satellite to measure light coming from Mercury's atmosphere; we were looking for elemental fingerprints in the frequency spectrum. Atoms are very picky about which frequencies of light they will interact with, and every element absorbs or emits light at such specific frequencies that they make a fingerprint. Our satellite would search for these fingerprints to tell us what Mercury's atmosphere is made of. (These frequency fingerprints correspond to the quantum energy levels in the atom's electron orbitals.) For instance, bands of light at 587.5 nanometers (nm), 504.7nm, and 706.5nm are notable in the fingerprint of helium; sodium's fingerprint has a remarkable pair of double yellow lines at 588.9nm and 589.6nm. Several atomic fingerprints are shown in figure 1 at right.

Figure 1: Spectral Fingerprints of Several Elements.

The frequencies of these fingerprints are mind-bogglingly fast. The photons in those double yellow lines of sodium are cycling five hundred trillion times every second, so when we measure these fingerprints, we only need a snapshot of the light. That frequency is so fast that we can capture it instantaneously with a measurement that has no real duration at all.

Of course, light can also carry oscillations that are much, much slower. Radio waves are a form of light, usually with a frequency of a few million cycles/second (much slower than visible light but still really fast!) When we talk over the radio, we actually modulate these waves with even lower frequencies that correspond to the range of human hearing—as low as 20 cycles/second. These frequencies are getting lower and lower, but they're still fast enough that we can measure them pretty much instantaneously. My radio converts even the lowest audible frequency into sound that my ear can hear "in real time."

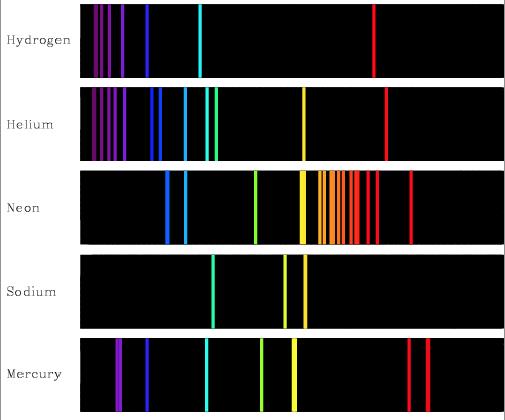

There's nothing special about these frequencies that are fast enough for us to perceive in real time. Light also carries information at such low frequencies that we must take measurements over a long period of time in order to perceive it. Sunlight for instance—in addition to the spectral fingerprints that can tell us what elements are present in the Sun—also carries ultra-low frequency information in its sunspot cycles, which have a period of about eleven years. We have observed this cycle by counting dark spots on the surface of the Sun, recording this data over hundreds of years, and then finding patterns in that data. The finding of this pattern is both the same and different from measuring the frequency of light coming from the Sun. It is different because generations of human observers are combining efforts to collect this data, but it is the same because there are indeed electromagnetic fluctuations in the Sun's radiation at this frequency.1 Obviously, there's no way to notice that sunspots occur in eleven year cycles unless we measure them for at least 22 years, because we'd need two cycles to establish a pattern. As it turns out, we've been observing sunspots for over four hundred years. I've plotted 180 years of this data below; the 11-year cycle is clearly visible (figure 2).

Figure 2: recorded sunspot number, 1840-2020.

We could think of the sunspot cycle as another kind of spectral fingerprint. Just as sodium marks light with its characteristic double yellow band—advising us of its presence and giving some insight into its atomic structure—the sun cycle marks light with precise frequencies that provide a glimpse into the Sun's internal structure and that are likely unique to our star. Certainly, we measure these ultra-low frequency variations differently than we measure different colors of light, but that's an accident of biology. We could imagine a giant intergalactic star-eater who would perceive this 1/11 year cycle in the Sun's electromagnetics as a shade of the color blue. Maybe blue stars are her favorite.

Engineers Don't Understand.

It's apparent that we can't say we understand the Sun unless we have an explanation for this eleven year cycle. Even if we identified the fingerprints of every element in the Sun and recorded their precise amounts, this reduction of our star to its elemental ingredients might not provide a model for the eleven-year sun cycle, and so our understanding would be obviously incomplete. Also, since the sun cycle is completely unobservable in real time, this makes it impossible to fully understand the Sun unless we have observed it for at least twenty-two years. (It actually appears that there are even more subtle dynamics present in sun cycle data, so even longer observations might be necessary).2

If we had only a few years of data, the sun cycle might appear as an ever-increasing or ever-decreasing trend—not cyclical at all. Limited by our short observation and unable to know about the cyclic nature of our data, we would have no window into the underlying cause of these trends. We might, however, easily convince ourselves that we do understand them. Armed with our reduced real-time understanding of the Sun, we might correlate some element or molecule with the increasing number of sunspots. Our engineers could even propose ways to manipulate the number of sunspots by controlling some related aspect of the Sun's structure. This manipulation would be entirely possible for engineers armed only with real time observations and very brief data sets that are much shorter than the sun cycle—ie, a very incomplete understanding of the Sun.

Generally, in order to claim understanding of a pattern such as the sun cycle, we would want to match that pattern to another one of equal frequency; scientific theories are built on this kind of pattern matching. So, for example, if a mathematician-physicist created a computer simulation of chemical and nuclear reactions taking place in the sun, and if that simulation predicted the eleven-year sun cycle, then most scientists would claim that we now understand this pattern, and our theories about nuclear reactions, fluid dynamics, etcetera would be confirmed. Understanding usually means the relation of two (or more) phenomena with equal frequency such that we can say these phenomena are essentially the same. This form of understanding provides insight into the underlying structure of whatever we're studying, but it is totally unnecessary for us to have this understanding in order to engineer or manipulate the object of study.

Look at All the Patterns

The frequency fingerprints revealed in sunspot counts are slow moving, but it appears that they are just as important as the faster prints of an element's spectral lines. Both sets of frequencies tell us about the internal workings of the Sun and how it is connected to the Earth. We must form our picture of the Sun based on all of this information together—the low and the high frequencies. I think this is essentially true of any phenomenon we care to study.

We could apply this concept to other data sets that seem important, and particularly to anything that we might be inclined to engineer or tamper with. We wouldn't want an engineer—however brilliant—tampering with the Sun if he only had five years of data. He might be pretty confident, because five years seems like a lot of data; maybe it's more than any of his peers have. He might have some pretty flashy ideas, but he literally can't know about the sun cycle. Without this missing information, he might mess something up.

I think, when we are going to manipulate something, it is wise to look at the patterns in the data we're about to use, and make sure that we understand patterns at every frequency where patterns are present. If we don't do that, any claim to understanding we make is absolutely fraudulent. Fortunately, it's pretty easy to make sure we haven't missed any patterns, because a mathematician named Fourier invented a way to find every pattern in any set of data and list them by frequency. (Actually even the Babylonians had started doing something like this, so it's not new). This means that if you give me any set of data, I can use a Fourier Transform to list all of the patterns in that data at every frequency. Mathematically speaking, that list and your original data would be equally complete representations of whatever you are measuring.3

What if every graph you ever saw showing data over time came along with another graph plotting that data against its frequencies? This would allow you to correlate all of the patterns in that data with other patterns that occur at the same frequencies. If we did that, would we uncover hidden information? Would the object of our study contain fingerprints analogous to the spectral lines I once sought in Mercury's atmosphere? Are there meaningful insights to be found in the frequency spectrum of say, COVID death rates? CO2 ppm in the atmosphere? The GDP? Our personal finances?

Fingerprints of Babylon in COVID Pathology

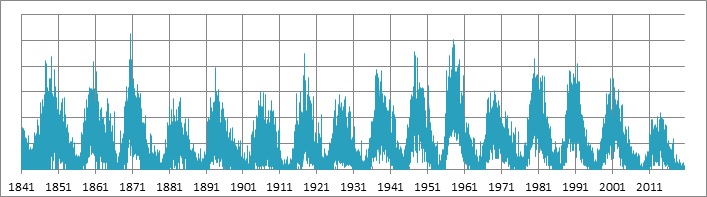

Figure 3: COVID infections and related deaths in GA as a function of time and frequency.

As a beginning to the exploration of these questions, let's look for frequency fingerprints in information about COVID infections and COVID-related deaths. I have plotted this information for my home state of Georgia as a function of both time and frequency at right (figure 3). The time plot (top) shows infections increasing through the summer, dropping slightly in the fall, and then beginning to climb again into the winter.4

These trends over time are not immediately apparent from the frequency plot (below), where the most obvious features are the peaks at 0.144/day and 0.288/day, which are present in both data sets. These are the frequencies of 1/week and 2/week (1/0.144 = 7 days), and they reflect lower reported death and infection rates on weekends. (These peaks do not correspond to 1 death/week or 1 case/week. They mean that the data contains a strong pattern that repeats itself once/week and twice/week, respectively)

Don't Die on Sunday

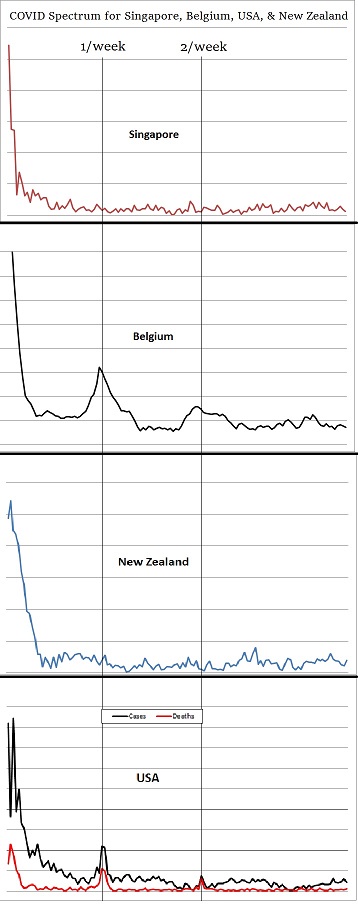

Figure 4: Frequency is on the horizontal axis for all plots.

My initial response to these two peaks in the frequency data was to discard them as an accident of the way that data is reported—essentially noise—but upon reflection I realize that they might have more meaning than I originally thought. I have come to think that trying to understand the COVID pandemic without appreciating these cycles is like trying to understand the Sun without the sun cycle. I am particularly convinced of their significance by my discovery that these peaks also exist in COVID data at the national level and in data for other nations. Further—and most important—the strength of this weekend fingerprint in a nation's COVID data appears related to the effectiveness of that country's response to the pandemic. In figure 4, I have plotted frequency spectrum of COVID data from two countries that have been lauded for a strong response to COVID: Singapore and New Zealand; and two countries whose poor response has led to many deaths: The USA and Belgium.5 The foundering countries have clear weekly periodicity, but these fingerprints are missing from Singapore and New Zealand's spectrum—the countries that have fared better.

Obviously, analysis of spectrum from one US state and four nations is insufficient to draw sweeping conclusions, but it seems possible (and even likely) that a meaningful correlation between this weekly fingerprint and a nation's COVID response could exist. I'd love to analyze further data sets, but this work is tedious, time-consuming, and I have no assurance that anyone will care. I've seen what I need to see. I'd suggest that further work should be undertaken by a student intern at the CDC or WHO in a paid position similar to the one I had baking sensors at LASP.

Our engineered response to this pandemic reacts to the particular virus that appears to have caused it. In many ways, this is like trying to manipulate the Sun with only information in the high frequency elemental fingerprints. The severity of the pandemic is very dependent upon slower-moving cultural factors that have nothing to do with the virus itself. (That's why some countries suffer more than others.) We can't equate the pandemic to the virus, and any engineered response to the pandemic should account for cultural patterns that make it up—just as attempts to manipulate the Sun would be more informed if they accounted for the sun cycle.

Beware the Turtle

When we look at these frequency plots, we also see that most of the information in the plot is crowded into the leftmost peak at the lowest reach of the frequency spectrum. This peak in the low frequency patterns means that our data set isn't long enough. This is what the patterns would look like in four years of sunspot data; it's not enough to establish the pattern.

Of course our COVID data is limited, because this is a new virus, but I think this preponderance of low frequency information also means that COVID is part of something else. Something bigger and slower moving. For example, we could have a much longer data set if, instead of studying infection with COVID, we studied infection with viruses in general. Or perhaps we should study other factors—comorbidities that predispose people to infections and poor outcomes. We may not be asking the right questions; we might be focusing our attention too closely upon something small that moves quickly, but something big and slow is hiding there on the left like a turtle in its shell. We'd have to do a much broader study covering a much longer period of time for this turtle in the data to come out, just like we'd have to observe the Sun for many more years to find the meaning of the trends in four years of data.

Don't think for a minute that this turtle's shell will be pierced by our needles. Vaccines are good things in many ways, but this pandemic can't be reduced to the virus. If we push it away with needles, it will simply return, but we can't say in what form unless we coax this turtle out of its shell by placing our study in the context of something longer and slower.

The Moon is Pissed

The 1/week band in the COVID spectrum is indeed the echo of a very long story. It is an artifact of the same Babylonian society that originated this method of breaking data into different frequency patterns, for it was their astronomers that first introduced the seven-day week, with one day each for the Sun, the Moon, and the five planets visible with the naked eye. The Babylonian week, however, would not have left fingerprints such as these in measurements of our pathology, for it was tied more directly to the 29.5 day lunar cycle; the lunar cycle being indivisible by seven, the Babylonians introduced one or two extra days each month to realign the weekly cycles with the new moon. These 'days out of time' would disrupt the exact seven-day cycle. The Hebrews modified the Babylonian week (or came up with it on their own, depending on your historical source) to develop a strict seven day week that was completely divorced from lunar influence; when that modification was formally adopted by the Roman Empire, it became widespread and apparently permanent.6

That is the story that marks our pathology data today. If this data matters, then that story matters, because it is a clear and remarkable aspect of the data. Is our synchronization to the weekly grind a pathological rhythm? How might it be a detriment to public health? It's true that our seven day week is primarily an economic consideration that would be disrupted by COVID shutdowns. It's almost as though the Moon has taken offence at our disregard, and now every 'day out of time' we've refused to observe has come back to haunt us. Perhaps we'll have to take them after all—and all at once.

I think one value of the analysis that I present here lies in its potential to challenge our metaphors and the way that we perceive meaning. The time and frequency plots are equally complete presentations of this information. Whatever it is that causes lowered death and infection rates to be reported on weekends, that dynamic is a primary feature of this data, and it should not be filtered out. By placing our attention upon the patterns present in our data, the frequency analysis I am presenting reveals the fingerprints of slower-moving—but equally important—causes of the pandemic as a whole. If we will engineer our response to the pandemic from a more complete understanding of the data, we must understand and address all of the known patterns. Seeing also that some patterns can't be perceived from this limited data set, we must actively seek other questions and ways of perceiving our predicament that illuminate even slower moving patterns.

'Just' a Metaphor

A traditional and rationally minded scientist might reasonably object to some of the connections that I have drawn in analyzing all of this data. The ever-increasing number of COVID related deaths might seem unconnected to the logistics of reporting hospital deaths on Sundays. Calendars don't cause pandemics! What's this about the Moon? If you have spectacles, you may now regard me over their rims.

Most people are accustomed to very reduced and mechanical explanations that allow us to understand things in real time. Pandemics are caused by viruses; sun cycles are caused by nuclear reactions between elements in the Sun; everything has a cause, and it is always something that we can see or perceive directly in real time. This belief is an arbitrary cultural construct. Patterns like the sun cycle exist in their own right. Once observed, they are equally real whether we reduce them or not, and may even be posited as the cause of other phenomena.

If we study Mercury's atmosphere and find double yellow lines at 588.9nm and 589.6nm, we recognize sodium's fingerprint, and that element becomes part of our vocabulary to describe reactions or activity on that planet. When we study the Earth's magnetic field and observe an eleven-year cycle in its magnitude, we relate that cycle to patterns we've found by counting dark spots on the Sun, and this informs us about Sun-Earth relations. When I study the COVID pandemic and find a 0.144/day band in the spectrum of our data, I recognize it as the fingerprint of a culture whose unwavering devotion to economics precludes synchronization with natural cycles such as the Moon's. When I correlate the strength of that frequency band with the success of a nation's COVID response, I learn about the role of economically determined calendars in the severity of a pandemic—a factor which actually has little to do with a virus.

I expect a temptation among my readers to explain away or rationalize my conjectured relation between weekly frequency bands in a nation's COVID data and national response to the pandemic (perhaps because I feel that temptation myself). Maybe it seems natural—and hence meaningless—that nations who take the pandemic most seriously will disrupt their weekend routines to focus on gritty details like after-hour paperwork on a Sunday. Perhaps nurses from nations that play down this crisis are eager to get home for the football game that hasn't been cancelled. But all this rather begs the question of why these cultures are loathe to disrupt that routine. It doesn't make the routine go away; I think it rather reinforces it.

We are Out of Time

We look for our explanations always in things that we perceive in real time. We celebrate or condemn a nation's leader (especially as it suits our political agenda); we take notes of who is or isn't wearing a mask; we await breathlessly the sacred vials of our saviors. And we punch the fucking clock from Monday till Friday.

This weekly pattern that hides in our pandemic data is a thing. It is absolutely as real as the sun cycle or Mercury—the planet or the element. I strongly believe that any attempt to engineer a social, medical, or biological response to this pandemic will not appreciably benefit long-term public health unless it responds to—and probably modifies—the weekly pattern in our society as whole. Attempting to engineer a response that fails to explicitly treat this aspect of the pandemic is like engineering a satellite that must negotiate changes in geomagnetic fields without factoring in the sun cycle. It'll work for a few years and then get dragged down when solar activity heats the upper atmosphere. I think it's also likely that our response must also acknowledge those even longer cycles and patterns that aren't directly perceivable in the few months of COVID data we have, but whose presence can be deduced from the preponderance of low frequency information.

Call me crazy, but what if a society that enjoys great public health must actually live in synchronization with natural patterns of the Earth, Moon, and the cosmology as a whole? Like, what if we must actually get in time with natural patterns as part of our most mundane routines in order to manifest a healthy and happy society? That's more than possible, you know.

Our culture's peculiar failure to get in time with long biological and geological patterns has a lot to do with our science and our metaphors about concepts like time. Modern civilized humans tend to think of time as a line with the past disappearing into infinity behind us and the future leading on ahead. That metaphor has been apparently useful so far, but we tend to forget that it's an abstraction, and that other cultures (whom we've unfortunately attempted to exterminate) used entirely different metaphorical maps to understand time.

Flat Maps

What might these other metaphorical maps of the world look like? There have certainly been other cultures—mostly victims of modern genocides—that don't (or didn't) see themselves as inhabiting a world of things. There have been other cultures who inhabited a world of recurring patterns, many of which are slow-moving and imperceptible in real time. This worldview produced an entirely different conception of time, once common among numerous cultures around the world, in which time is not the linear concept we now entertain, but rather a circular and repeating phenomenon that reflects seasonal, biological, and cosmological cycles.7

While I am cautious of speaking for cultures that are not mine, I believe it is safe to say that scientists from these cultures might be (or have been) quite comfortable attributing the causes of big crises like the COVID pandemic to slower-moving patterns that aren't directly perceivable—assuming that such patterns have been detected by long measurements. Anyway, there are plenty of first-hand accounts by such scientists that are less enamored by things and that point to deep cultural roots of our crises, so you don't have to take my word for it.8

I don't feel like I'm going out on a limb when I say that scientists from cultures who don't even share our concept of linear time might find more useful information in the bottom half of figure 3 (the frequency plot) than they do in the top. The frequency plot acknowledges the inevitably cyclic nature of this phenomenon, while the time plots distort that aspect of our object like a flat map. We shouldn't sail near the poles with a Mercator projection of the Earth, nor navigate the COVID crisis with data sets plotted as trends over short periods of time.

The World We Live In

We live in an extremely abstract world of words. It appears to be an almost universal human experience to spend much of one's time in active thought with words running through the mind. These words are all metaphors, and as the linguist Guy Deutscher points out, most of them have become unmoored from their physical origins: the words behind and ahead are spatial metaphors frequently exported from that domain to apply to our linearized notion of time. When we hear them today, these words barely connote their even earlier origins as metaphors referencing parts of the body. Many other words have become so abstract that their roots in concrete reality are relegated to academic journals. We forget they were ever metaphors at all, but those roots are always there.9

We also forget that the language of science is metaphorical. As Nietzsche observed 150 years ago (and many others before and since), "every concept originates with our equating what is unequal." Science amounts to the adoption of "customary metaphors—an obligation to lie according to a fixed convention."10 We talk about COVID deaths as if they're all the same, but they're not. Each person who dies of or with COVID has a different health history, different career, and different social network. There are a whole slew of factors that undermine or fortify our personal resistance to this pandemic, and to equate the death of one person with the death of another is an abstraction. It is a metaphor. We must concede the metaphorical expression of reality, even in science. (This doesn't mean we shouldn't have concepts and metaphors. There is a post-modern tendency to violate every concept that ever existed—at least the inconvenient ones—on the principle that no concept is perfect. That isn't what I'm talking about.)

In forgetting that our perception and science are metaphorical, we have created a situation where we simply can't notice when our information is distorted by those metaphors. On top of this, through centuries of genocide and cultural erasure, we have made it very unlikely that we will ever encounter metaphorical maps that differ noticeably from our own. Now, our metaphors are failing, and our civilization is in crisis. It's very likely that a viable response to our crisis will require information seriously distorted by the metaphors of modern science and culture. Our problems are so large that we cannot approach them using small, reduced patterns that are perceivable in real time. This means that we are faced with the task of substantially reworking our understanding of the world in the near vacuum we've created by systematically expunging other cosmologies, other languages, and other systems of metaphors that may have provided well-proven templates.

I believe it is imperative that we begin to see ourselves as an inextricable part of a polyrhythmic cosmology wherein every phenomenon is composed of multiple repeating cycles. We must greatly deemphasize our linear conception of time or abandon it altogether. In order to do this, we will probably need to materially acknowledge the terrible tragedy of our genocidal history—and the reality that this history isn't 'gone' into some abstract past. That's a tall order, but I believe it's an honest assessment of the challenges now facing modern civilization.

Endnotes

1. Spectral fingerprints in light are also equivalent to sunspot data in the sense that frequencies of light are statistical quantized phenomenon, as are sunspot measurements. There are spotless days even during the peak of sunspot cycles, and patterns emerge only from years-long measurements; neither are individual photons of light constrained to patterns that nonetheless define the frequency of the wave they belong to.

2. If we do a frequency analysis on sunspot data (such analysis explained in following sections) we can see peaks of information at about 1/85 years in addition to the strong 1/11 year cycle. Jean Feynman demonstrates evidence for a 1/87 year cycle in Feynman, J. "Geomagnetic and solar wind cycles, 1900-1975", Journal of Geophysical Research., 87, 6153-6162, 1982.

3. For further exploration of Fourier transforms, you might check out this interactive simulator that allows you to enter data and view the waves that produce that data, or to enter a series of waves and see the data it produces. It's very interesting.

4. This data set covers the period from March 2020, when the first COVID-related death occurred, to the beginning of December 2020. COVID Data for the state of GA provided by the GA DPH. Fourier transforms for frequency calculations are my own. These Fourier transforms require that the number of samples in the data sets be a power of 2. GA DPH has data for 324 days at this writing. The closest power of two that works for my calculations is therefore 256 days, and I have chosen to begin the analysis from 3/22/2020, which is the date of the first COVID related death in the state. When and if there are 512 days of data, I would be able to extend the analysis to cover the larger data set. A more complete analysis than this should cover additional 256-day windows of time or employ other methods allowing the full data set to be used.

5. Global COVID data provided by Our World in Data. Frequency calculations my own.

6. Whitrow, G.J. Time in History: View of Time from Prehistory to the Present Day. New York: Barns and Noble. 2nd ed, 2004. Whitrow cites sources indicating that the 7-day Hebrew week could have been adopted from Babylonian calendars or developed independently.

7. I have written about this extensively elsewhere. For example in Feather, Paul and Currie, Terra. Quantum Justice: Theories and Theatrics for the Ecozoic Era. Carrollton, GA: Full Life Farm Publications, 2018. "The Hopi people of Arizona, the Azande of Southern Sudan, the Nuer of the White Nile in Sudan, the Ahnishinahbæótjibway of the upper Midwestern U.S., the Aboriginal Indigenous of Australia,the Tlingit of Alaska, and the Dagara of West Africa...all had completely different conceptualizations of time... For many of these people, time is structured as a repeating, circular model reflective of seasonal changes." For information about of some of these perspectives on time, see Whitrow, G.J. Time in History: View of Time from Prehistory to the Present Day. New York: Barnes and Noble. 2nd ed, 2004. Whitrow includes studies of Hopi, Australian Aboriginal, Ugandan, Sudanese, and other perspectives. More complete (and first hand) descriptions of time awareness among the Dagara people can be found in Somé, Malidoma Patrice. Ritual: Power, Healing, and Community. New York: Penguin, 1993; the Ahnishinahbæótjibway in Wub-e-ke-niew. We Have the Right To Exist: A Translation of Aboriginal Indigenous Thought The first book ever published from an Ahnishinahbæótjibway Perspective. New York: Black Thistle Press, 1995; Australian Aborigines in Peat, D. Lighting the Seventh Fire. Secaucas: Carol Publishing, 1994. pg 287; the Tlingit in Dauenhauer, Nora Marks. and Dauenhauer, Richard. Haa Shuká, Our Ancestors: Tlingit Oral Narratives. Seattle: University of Washington Press and Juneau: Sealaska Heritage Foundation. 1987

8. Our concept of time is explicitly treated as a cause for crisis and genocide in Wub-e-ke-niew (above). See also Cajete, Gregory. Native Science: Natural Laws of Interdependence. Santa Fe: Clear Light Publishers, 2000. Cajete specifically treats cosmology as a defining factor in our multiplicity of crises. Also Kimmerer, Robin. Braiding Sweetgrass. Milkweed Editions, 2015. Among other things, Kimmerer cites mechanical worldviews and departure from relationships founded in reciprocity as causes of environmental collapse, etc. These native scientists—and many others—attempt to treat broad and abstract cultural constructs.

9. Deutscher, Guy. The Unfolding of Language: an Evolutionary Tour of Mankind's Greatest Invention. New York: Picador, 2005.

10. Nietzsche, Friedrich. "On Truth and Lie in an Extra-Moral Sense" published posthumously, 1873. In ed. Kaufmann, Walter. The Portable Nietzsche. New York: Penguin, 1954.